As Nairobi County comes under new management, Ruto-Sakaja pact reignites NMS ghosts

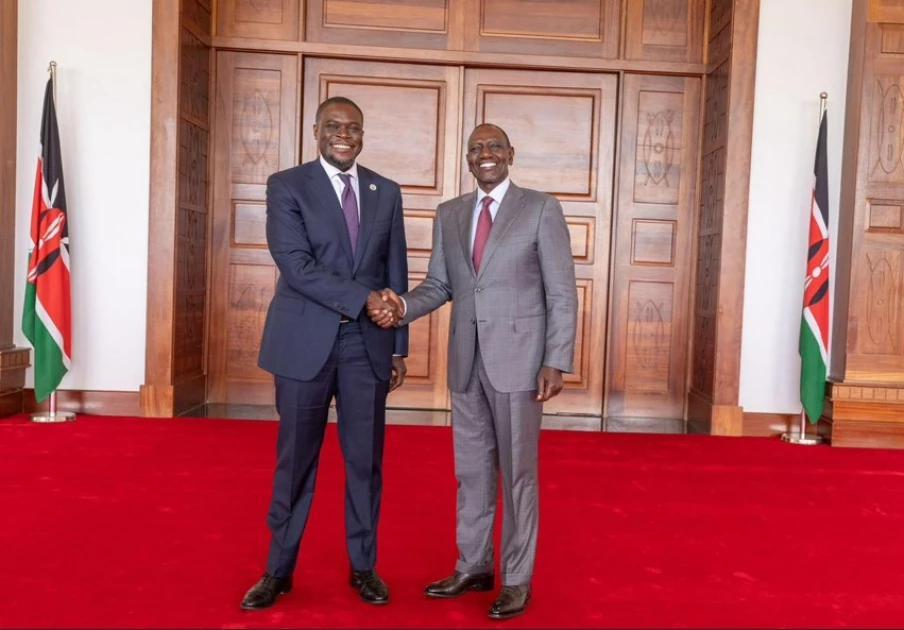

President William Ruto and Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja shake hands at State House, Nairobi on February 17, 2026.

Audio By Vocalize

The ceremony was formal, the language carefully calibrated. Officials called it a "cooperation" pact. Critics called it a coup. And many veteran observers of Nairobi’s turbulent political history called it something else entirely: a replay of the NMS.

The KSh80 billion framework agreement between the National Government and Nairobi City County has ignited one of the fiercest constitutional and political debates Kenya’s capital has witnessed since the militarised transfer of functions that effectively neutered then-Governor Mike Sonko in 2020. At the heart of the controversy lies a deceptively simple question: is this a partnership to rescue a struggling city, or a calculated takeover of its most lucrative functions?

The Architecture of the Deal

Under the cooperation framework, the National Government assumes financial and operational responsibility for a sweeping set of functions that have long been constitutionally vested in Nairobi County. These include solid waste management and waste-to-energy initiatives, road construction and rehabilitation, water and sewerage infrastructure, public lighting, drainage systems, affordable housing, and the regeneration of Nairobi’s rivers; the last two being among President Ruto’s signature policy priorities. The handover of these functions is to take effect within fourteen days of the signing.

Governance of the arrangement rests on a two-tier structure. A high-level Steering Committee, chaired by Prime CS Mudavadi and including senior Cabinet Secretaries, the Attorney General, and Governor Sakaja as Vice-Chair, will provide strategic oversight. Below it, an Implementation Committee chaired by the Governor himself, and comprising both national Principal Secretaries and County Chief Executive Committee members which, is tasked with day-to-day execution. The Governor and the President have been emphatic: legal ownership of the mandate and county staff remain with City Hall. Nairobi, they insist, has not been handed over.

But the critics are not persuaded. Nairobi Senator Edwin Sifuna has been the most vocal, describing the agreement as a "power grab through the back door." His central objection is procedural and constitutional. He asserts that the Senate, whose primary mandate is the protection of devolution and county governance, was never consulted. Neither, he argues, was the public, which is a requirement enshrined in Kenya’s constitutional framework. Crucially, Sifuna points to the composition of the Steering Committee itself; out of its twelve members, eight are appointees of the National Government, this is a direct give-away of the path ahead.

Echoes of Sonko: History Rhymes in Nairobi

The resonance with 2020 is difficult to ignore. When President Uhuru Kenyatta’s administration engineered the transfer of functions from then-Governor Mike Sonko, the mechanism was a formal Deed of Transfer that handed Health, Transport, Public Works, and Planning to the newly created Nairobi Metropolitan Services, a military-led body commanded by Major General Mohamed Badi. Sonko, who later claimed he had been coerced, found himself reduced to a figurehead. The writing was on the wall; he simply failed to read it before an impeachment motion sealed his fate.

The structural parallels between the two eras are striking. In both cases, the immediate trigger was the failure of city management on matters waste collection, dilapidated roads, inadequate water and housing infrastructure. In both cases, State House exerted decisive influence over the city’s governance calculus. And in both cases, the underlying premise was that Nairobi, as a regional commercial and diplomatic hub of continental significance, is simply too consequential to be left to the uncertainties of county administration alone.

The differences, however, are legally and politically significant. The 2020 arrangement was executed through a formal Deed, giving NMS an effectively independent operational mandate from which the Governor was excluded entirely. The 2026 framework deliberately sidesteps the Deed mechanism, choosing instead to anchor itself in Section 6 of the Urban Areas and Cities Act, which recognises Nairobi’s unique status as the seat of the national government and a global diplomatic hub.

Governor Sakaja’s administration frames this not as a transfer of functions under Article 187 of the Constitution, which would require rigorous approval from the County Assembly and the Senate, but as a cooperative arrangement that leaves constitutional responsibility intact with the County.

Constitutional Threshold and the Legal Battle Ahead

Whether this distinction survives judicial scrutiny remains to be seen. A petition filed in the High Court has already been certified as urgent and is scheduled for hearing on March 16, 2026, with two activists arguing that the pact violates constitutional provisions on public participation and the spirit of devolution.

Meanwhile, the Katiba Institute has written formally to the Nairobi City County Secretary under Article 35 of the Constitution and the Access to Information Act, demanding full disclosure of the legal basis, scope, financing, and the County Assembly’s involvement in the agreement. The Law Society of Kenya has separately warned that the KSh80 billion framework risks becoming a cousin of the discredited NMS model.

The financial questions are equally pointed. The NMS era concluded leaving behind KSh16 billion in pending bills, a blot and a cautionary tale that Senator Sifuna has been quick to invoke when questioning where the new KSh80 billion will originate and how it will be accounted for.

The 2026 agreement claims to route expenditure through the existing Public Finance Management Act framework, offering legal channels for money flows rather than the opaque standalone fund that characterized the NMS period. Whether this commitment holds in practice will be the defining test of the deal’s credibility.

The Political Undercurrents: Sakaja, the MCAs, and 2027

Astute political observers have traced the conditions for this pact to a near-impeachment drama that unfolded in September of last year, when Members of the County Assembly assembled the numbers to remove Governor Sakaja from office. The motion was halted after summons from State House; Sakaja was counselled, the MCAs were stood down, and survival came courtesy of interventions from the late ODM leader Raila Odinga and President Ruto.

Further, some analysts allege that elements within the national government had been quietly facilitating county services such as resurfacing roads, laying paving blocks, collecting waste way before the formal pact, and that the agreement is essentially the legalisation of an arrangement already in motion.

The irony is that the pact, which may have been partly designed to stabilise Sakaja’s political position, appears to have destabilised it further. The MCAs, far from being appeased, have declared that the cooperation framework was concluded without their knowledge or blessing, and have assembled a fresh committee to scrutinise the agreement, evaluate its budgetary implications across two financial years, and enable public participation all within a window of less than a fortnight. The question of whether Nairobi is about to impeach its second consecutive governor is no longer rhetorical.

Opposition leaders have not missed the political valence of the timing. With the 2027 general election on the horizon, critics such as MP Babu Owino have characterised the KSh80 billion as potential campaign fuel, describing the deal as an expressway to "unfettered looting" in the run-up to the polls. The broad-based government coalition has predictably pushed back, praising the pact as long overdue and essential for service delivery to the millions of residents of a city that hosts the United Nations and serves as East Africa’s commercial nerve centre.

Accountability in the Shadows: Who Answers to Whom?

Perhaps the most consequential unresolved question in the entire arrangement concerns accountability. The Steering Committee, chaired by Prime CS Mudavadi, is not clearly tethered to any specific oversight body. It is ambiguous whether it reports to Parliament, to the County Assembly, or directly to the Presidency.

This ambiguity extends across the governance chain: can the Nairobi County Assembly summon the committee or its officials to account for expenditure and service failures, or does scrutiny rest exclusively with Parliament? In the event of a service delivery breakdown, where does responsibility lie? Is it with the Governor, the committee, or the national executive?

The fate of existing county contracts, including those for garbage collection and ongoing infrastructure works, also hangs unresolved. Leaders who have scrutinised the deal warn that overlapping mandates will complicate the work of the County Assembly, the Senate, and the Office of the Auditor General, potentially creating the conditions for grand corruption on a scale that would dwarf the NMS scandals.

For now, the President and the Governor hold their line: this is cooperation, not capture. But as Nairobi’s County Assembly scrambles to assert its constitutional role, as the High Court prepares to adjudicate, and as civic bodies demand transparency on a deal that will reshape the governance of Africa’s fourth-largest city, the semantics of "cooperation" may prove to be the least of the pact’s problems. What is unfolding, with or without the blessing of the Constitution, is a fundamental contest over who truly runs Nairobi, and for whose benefit.

Leave a Comment