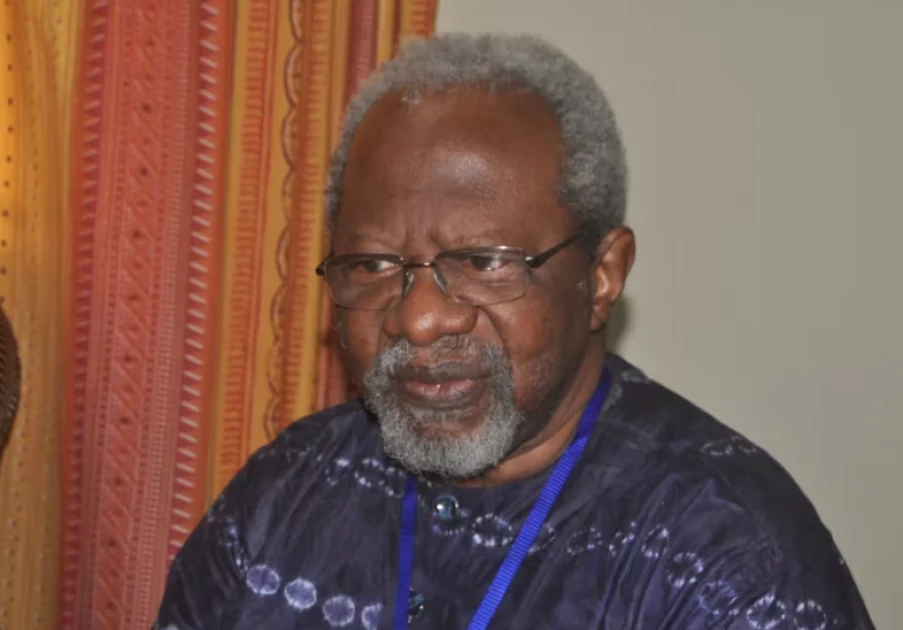

At 80, Paulin J. Hountondji is one of Africa’s greatest modern thinkers

Paulin Hountondji….the anointed enfant terrible of African philosophy. Hountondji's personal collection

Audio By Vocalize

When

renowned Ghanaian philosopher Kwasi Wiredu passed

on in early 2022, Paulin J. Hountondji was left alone to adopt the mantle of

“Africa’s greatest living philosopher”. With one possible exception – Congolese

philosopher and historian of ideas, V.Y. Mudimbe.

Hountondji’s

long and gallant campaign to establish and disseminate an African philosophical

voice is noteworthy.

His

first book was 'African Philosophy: Myth and Reality' published

in 1976. It introduced an unapologetic and counter-intuitive African presence

into the supposedly scientific annals of world philosophy. This paradigmatic

entry includes a generous critique of the work of the hitherto forgotten 18th

century Ghanaian philosopher, Anton Wilhelm Amo. It is also an intricate

metaphilosophical critique and a strident evaluation of Kwame Nkrumah and Nkrumaist ideology.

His second book, published in 2002, was 'The Struggle for Meaning: Reflections on Philosophy, Culture and Democracy in Africa.' It revisits his earlier doctoral dissertation on the German philosopher, Edmund Husserl. It examines his engrossing trajectory as an African engaged in philosophy on the global stage.

Much

of the work is also devoted to replying to critics. This includes the late Olabiyi Yai. But Hountondji has nothing but

affection for the contributions of Congolese-born philosopher Valentin-Yves Mudimbe and Kwame Anthony Appiah.

Hountondji

comes across as the anointed enfant terrible of African philosophy. This is

even more so than Wiredu and the equally revered Mudimbe. He has criss-crossed

various metropolitan capitals spreading the mantra of African philosophy. He paradoxically

denounced the discourse of ethnophilosophy as a colonialist (pseudo)

disciplinary invention. At the same time he promoted philosophy’s innate

scientism and universalism.

Establishing

modern philosophy within the continent

His

academic career began in the early 1970s in Mobutu Sese Seko’s Zaire in the

cities of Kinshasa and Lubumbashi. He then returned to his country, Dahomey

(now Benin Republic) in 1972.

The

following year he was instrumental, alongside other continental colleagues, in

founding the Inter-African Philosophy Council. He was also crucial in

establishing early important journals on philosophy within the continent. They

include the _African Philosophical Notebook_s. And the council-affiliated

_Consequence: Review of Inter-African Council of Philosophy.

Part

of the effort in establishing modern philosophy on the continent entailed

forming trans-regional organisations. Sadly, these have withered with the

exception of the African Philosophy Society. Hountondji has supported it by

granting it legitimacy and serving as a keynote speaker at its events.

Ideologically

and theoretically, Hountondji’s version of philosophical universalism and

Africanity would have been a very hard sell for any other philosopher – except

for Hountondji himself. His stature has only seemed to rise. Indeed his support

for a Euro-Amer-defined philosophical universalism did not seem emancipatory in

an age of decolonisation and postcolonial despair. Philosophers were expected

to reveal there ideological stances. These were meant to be anti-imperialist

and pro-masses in orientation.

During

this period African philosophers were also expected to get their hands dirty.

This meant getting off the high horse of theory and abstraction to partake in

the onerous and messy task of nation-building.

In

other words, they had to take concrete measures to justify their sociopolitical

existence and relevance.

Hountondji

did eventually become a nation-builder. He held two ministerial portfolios in

the early 1990s in Benin Republic. After emerging from the torrid political

battles geared at consolidating Benin’s fledgling democracy, he returned to

academia. There he resumed his unfinished investigations into strictly

philosophical matters.

The

enfant terrible of yore had transformed into part of the venerable old guard.

This comprised Wiredu, Peter O. Bodunrin and late Kenyan

philosopher Henry Odera Oruka.

He

also became a highly sought and favoured guest at philosophical gatherings all

over the world.

He

has continued to publish his research on the state of scientific and

philosophical knowledge in Africa. And his stutter has not prevented him from

sharing his invaluable insights on his diverse areas of expertise.

Franziska

Dubgen and Stefan Skupien in their book (2019) on Hountondji argue

for his acceptance as a universal thinker. This is fair enough. But it is

always useful to remember that Hountondji popularised a few vital concepts and

subjects with a distinctly African flavour.

Notable

among them are the inevitable critique of ethnophilosophy, a repudiation of

unanimism, an assessment of Nkrumaism, the rehabilitation of Amo and the

searing indictment of scientific dependency. There is also the recent concept

of endogenous knowledge. This might indeed be considered as an endorsement of

the ethnographic potentials of philosophy, on the one hand, and the

valorisation of local knowledges, on the other.

Universalism

versus particularism

Philosophically,

Hountondji’s work is characterised by an ever-present contestation between

universalism (epistemic) and particularism (endogeneity). He avoids a neat

resolution simply because it is a tension that animates what is considered to

be philosophical.

The

source of the particular is invariably African. For its part, the universal is

ostensibly defined as Western. This equation has the possibility of

inaugurating an evident relativism which stands to be repudiated. This is

particularly true given the transcendent dimension of Hountondji’s thought. Indeed

the philosophical transcends the limitations of the particular.

The

relation of Hountondji’s work to decolonial thought was re-emphasised at a

recent workshop at the University of Cape Town. In an era of decolonial

theorising, Hountondji finds himself conveniently lumped with a range of

contemporary thinkers. These include Walter Mignolo, Andre Lorde, Gayatri

Spivak, Hamid Dabashi, Dipesh Chakrabarty and Achille Mbembe.

Undoubtedly,

this diversifies the canon of critical theory. It also ensures Hountondji’s

continuing relevance.

In view of these varied insights and contributions, Hountondji can congratulate himself for a life well-spent, thus far. And on attaining the ripe old age of 80 on April 11, 2022.

[The

writer, Sanya Osha, is a Senior Research Fellow,

Institute for Humanities in Africa, University of Cape Town. He does not

work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or

organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no

relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.]

Leave a Comment