For first time, Webb telescope discovers an alien planet

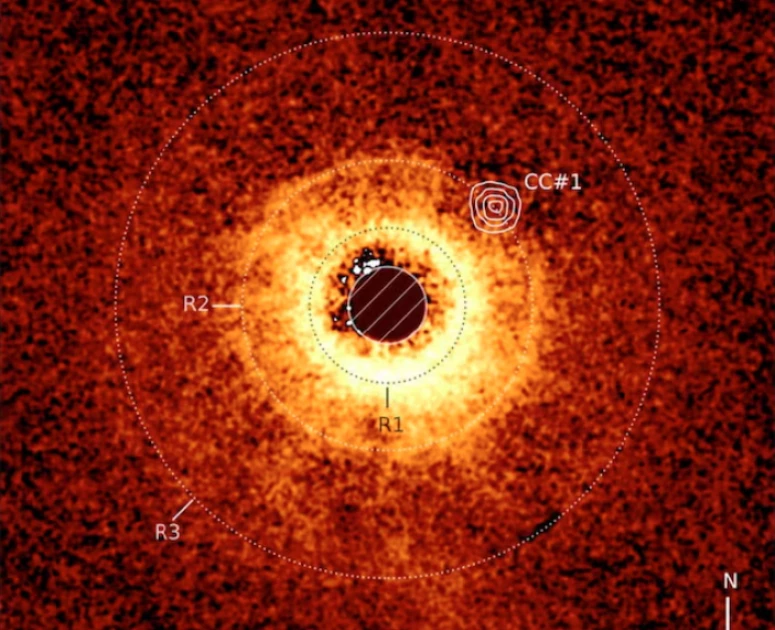

An image of the protoplanetary disk around the star TWA 7, recorded using the European Southern Observatory's Chile-based Very Large Telescope's SPHERE instrument, is seen with an image captured with the James Webb Space Telescope's MIRI instrument overlayed in this image released on June 25, 2025. The empty area around exoplanet TWA 7 B is shown in the R2 ring, CC #1. AM Lagrange et al/JWST/ESO/Handout via REUTERS

Audio By Vocalize

In addition to providing a trove of information about

the early

universe, the James

Webb Space Telescope, since its 2021

launch, has obtained valuable data on various already-known planets

beyond our solar system, called exoplanets.

Now, for the first time, Webb has discovered an exoplanet not previously known.

Webb has directly imaged a young gas giant planet roughly the size of Saturn, our solar system's second-largest planet, orbiting a star smaller than the sun located about 110 light-years from Earth in the constellation Antlia, researchers said. A light-year is the distance light travels in a year, 5.9 trillion miles (9.5 trillion km).

Most of the roughly 5,900 exoplanets discovered since the

1990s have been detected using indirect methods, such as through observation of

the slight dimming of a star's light when a planet passes in front of it,

called the transit method. Less than 2% of them have been directly imaged, as

Webb did with the newly identified planet.

While this planet is large when considered in the context of

our solar system, it is actually the least massive one ever discovered through

direct imaging, 10 times less massive than the previous record holder. This

speaks to the sensitivity of Webb's instruments.

This discovery was achieved using a French-produced

coronagraph, a device that blocks out the bright light from a star, installed

on Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI.

"Webb opens a new window - in terms of mass and the

distance of a planet to the star - of exoplanets that had not been accessible

to observations so far. This is important to explore the diversity of

exoplanetary systems and understand how they form and evolve," said

astronomer Anne-Marie Lagrange of the French research agency CNRS and LIRA/Observatoire

de Paris, lead author of the study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The planet orbits its host star, called TWA 7, at a distance

about 52 times greater than Earth's orbital distance from the sun. To put that

in perspective, our solar system's outermost planet, Neptune, orbits

about 30 times further from the sun than Earth. The transit method of

discovering exoplanets is particularly useful for spotting those orbiting close

to their host star rather than much further out, like the newly identified one.

"Indirect methods provide incredible information for

planets close to their stars. Imaging is needed to robustly detect and

characterise planets further away, typically 10 times the Earth-to-sun

distance," Lagrange said.

The birth of a planetary system begins with a large cloud of

gas and dust - called a molecular cloud - that collapses under its own gravity

to form a central star. Leftover material spinning around the star in what is

called a protoplanetary disk forms planets.

The star and the planet in this research are practically

newborns - about 6 million years old, compared to the age of the sun and our

solar system of roughly 4.5 billion years.

Because of the angle at which this planetary system is being

observed - essentially looking at it from above rather than from the side - the

researchers were able to discern the structure of the remaining disk. It has

two broad concentric ring-like structures made up of rocky and dusty material, and one narrow ring in which the planet is sitting.

The researchers do not yet know the composition of the

planet's atmosphere, though future Webb observations may provide an answer.

They are also not certain whether the planet, being as young as it is, is still

gaining mass by accumulating additional material surrounding it.

While this planet is the smallest ever directly imaged, it

is still much more massive than rocky planets like Earth that might be good

candidates in the search for life beyond our solar system. Even with its

tremendous capabilities of observing the cosmos in near-infrared and

mid-infrared wavelengths, Webb is still not able to directly image Earth-sized

exoplanets.

"Looking forward, I do hope the projects of direct

imaging of Earth-like planets and searches for possible signs of life will

become a reality," Lagrange said.

Leave a Comment