More evidence links a virus to multiple sclerosis, study finds

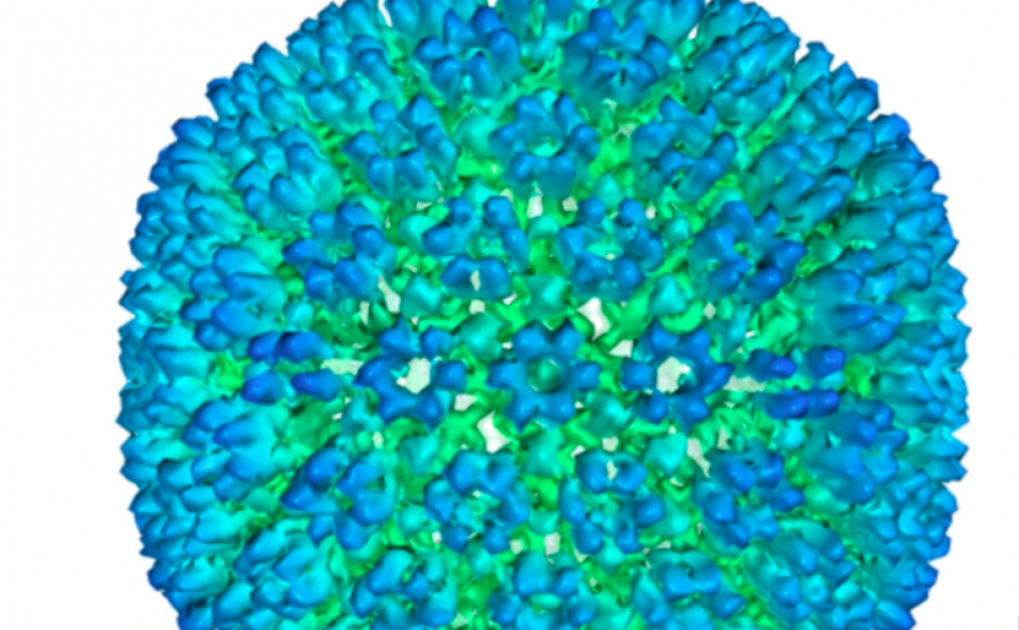

This image provided by US Department of Health and Human Services shows an illustration of the outer coating of the Epstein-Barr virus, one of the world’s most common viruses.

Audio By Vocalize

There's more evidence that one of the world's

most common viruses may set some people on the path to developing multiple

sclerosis.

Multiple sclerosis is a potentially disabling

disease that occurs when immune system cells mistakenly attack the protective

coating on nerve fibers, gradually eroding them.

The Epstein-Barr virus has long been

suspected of playing a role in the development of MS. It's a connection that's

hard to prove because just about everybody gets infected with Epstein-Barr,

usually as kids or young adults, but only a tiny fraction develop MS.

On Thursday, Harvard researchers reported one

of the largest studies yet to back the Epstein-Barr theory.

They tracked blood samples stored from more

than 10 million people in the U.S. military and found the risk of MS increased

32-fold following Epstein-Barr infection.

The military regularly administers blood

tests to its members, and the researchers checked samples stored from

1993-2013, looking for antibodies signaling viral infection.

Just 5.3% of recruits showed no sign of

Epstein-Barr when they joined the military. The researchers compared 801 MS

cases subsequently diagnosed over the 20-year period with 1,566 service members

who never got MS.

Only one of the MS patients had no evidence

of the Epstein-Barr virus before the MS diagnosis. And despite intensive

searching, the researchers found no evidence that other viral infections played

a role.

The findings "strongly suggest"

that Epstein-Barr infection is "a cause and not a consequence of MS,"

study author Dr. Alberto Ascherio of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public

Health and colleagues reported in the journal Science.

It's clearly not the only factor, considering

that about 90% of adults have antibodies showing they've had Epstein-Barr,

while nearly 1 million people in the U.S. are living with MS, according to the

National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

The virus appears to be "the initial

trigger," Drs. William H. Robinson and Lawrence Steinman of Stanford

University wrote in an editorial accompanying Thursday's study. But they

cautioned, "additional fuses must be ignited," such as genes that may

make people more vulnerable.

Epstein-Barr is best known for causing

"mono," or infectious mononucleosis, in teens and young adults but

often occurs with no symptoms. A virus that remains inactive in the body after

initial infection, it also has been linked to later development of some

autoimmune diseases and rare cancers.

It's not clear why. Among the possibilities

is what's called "molecular mimicry," meaning viral proteins may look

so similar to some nervous system proteins that it induces the mistaken immune

attack.

Regardless, the new study is "the

strongest evidence to date that Epstein-Barr contributes to cause MS,"

said Mark Allegretta, vice president for research at the National Multiple

Sclerosis Society.

And that, he added, "opens the door to

potentially prevent MS by preventing Epstein-Barr infection."

Attempts are underway to develop Epstein-Barr

vaccines including a small study just started by Moderna Inc., best known for

its COVID-19 vaccine.

Leave a Comment