The inside story of one man's five-year ordeal in an Iranian prison

Audio By Vocalize

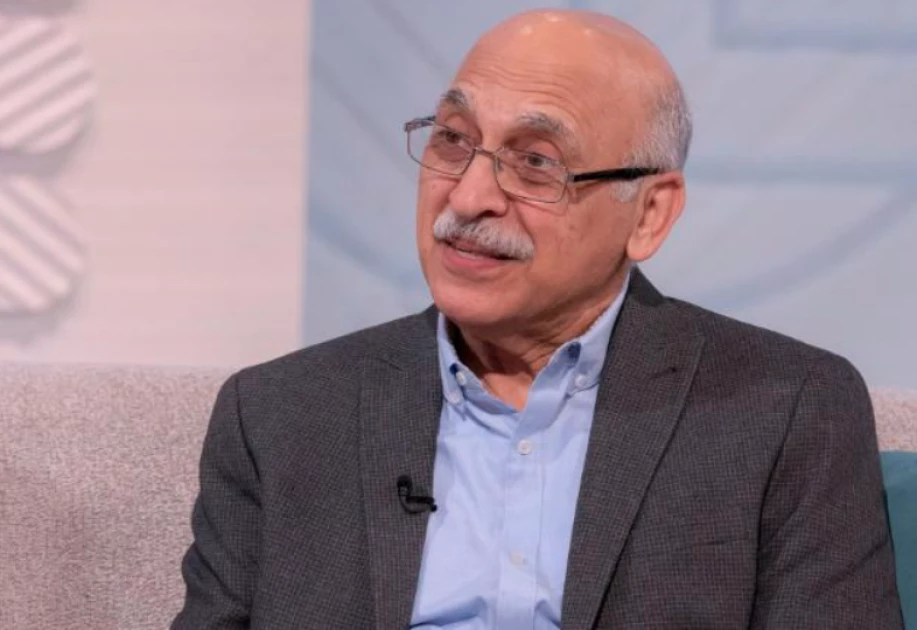

Anoosheh Ashoori points on a computer screen

to the location of a makeshift shelter in the yard of Tehran's notorious Evin prison.

"I used to sit here during winter and

even when it was snowing," Ashoori says in an interview with CNN's Becky

Anderson. It was here that he worked hard to create a semblance of normality

during an experience that was anything but ordinary.

The 68-year-old British-Iranian businessman

spent nearly five years at Evin on espionage charges. He was convicted of

spying for Israel's Mossad intelligence agency and sentenced to 12 years,

according to Iran state news agency IRNA. He insists he was wrongly convicted.

One month since he and British-Iranian aid

worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe were

released, Ashoori describes the anguish of leaving other dual-national

prisoners behind.

Upon his return to the UK, Ashoori says he received

an invitation to meet with the prime minister. He criticizes the UK government

for an "incomplete job" and says he will only consider meeting the

prime minister when the other prisoners are released. "You have paid 400

million pounds ($522 million) for two people," he says, addressing the

government. "What about the rest?"

The sum Ashoori refers to is a 40-year-old

debt the UK owed Iran. Ashoori and his family believe that had the UK

government paid it sooner, years of heartbreak would have been saved.

Despite being called a "ransom" by

Iran's critics, Tehran has denied any links between the payment of Britain's

debt and the release of two British-Iranian prisoners.

Iran's critics accuse the Islamic Republic of

holding Iranians with foreign passports as leverage in its conflict with

the West, arguing that innocent dual nationals become pawns in

the political wrangling between the two.

It was August 2017, Ashoori recalls, when he

left his home in South London to help his mother in Iran as she recovered from

a knee operation. As he walked down a hill in north Tehran to the local market,

four men jumped out of a car in front of him. They verified his identity and

sped away with him in the car. This was the start of a nearly five-year ordeal.

The following morning, Ashoori was allowed a

30-second phone call to his mother to tell her that he was in Evin prison. That

was followed by two months of total silence, his wife Sherry Izadi told CNN.

"We had no idea if he was alive,"

she said. "What was happening to him? Is he being tortured? Is he being

interrogated?"

"You don't need to be physically

tortured to go through hell," he told CNN.

His ordeal led him to consider suicide.

Ashoori says he tried slashing his wrists. When that didn't work, he tried

poisoning himself. And when that didn't work, he stopped eating. It was a

covert hunger strike, because as Ashoori tells it, "when you go on hunger

strike it is to protest something... but I just didn't want to be," he

says.

As he languished in prison, Ashoori's family

opted against speaking out publicly, thinking that diplomacy would be his best

chance for freedom.

"I knew that wasn't going to be productive,"

says his daughter Elika Ashoori. Two years after he was arrested, Ashoori was

convicted, and that's when his family decided it was time to begin campaigning

for his release.

His wife regrets not starting the campaign

sooner. "I should have started immediately after he was taken," she

says. "[I] urge all families to do the same because it's very easy to be

forgotten."

Following his suicide attempts, Ashoori was

moved into a different cell with other inmates who he began to bond with.

These groups, formed with other political

prisoners in what Ashoori jokingly referred to as "Evin university,"

involved discussions and workshops on physics, economics, poetry, Spanish and

marquetry.

These activities were one of the ways the

retired engineer stayed sane, sometimes managing to forget he was in prison

"because you were so engrossed in doing these things."

Ashoori emphasizes another group of

prisoners. "The environmentalists... Even there at Evin prison, they are

trying to promote the idea of saving the environment."

Siamak Namazi,

the Iranian American prisoner who has been imprisoned since 2016 alongside his

father Baquer, and who Ashoori describes as "a good friend and role

model," came to congratulate him ahead of his release. "He was...

genuinely happy that I was leaving. And I was so upset that I was leaving him

behind."

The fate of the remaining dual-national

prisoners remains uncertain as the geopolitical standoff between Iran and the

West continues.

For now, Ashoori is trying to move on with

life while campaigning for the release of the other prisoners.

"When you see others leave and you are

left behind, it's another torture."

Leave a Comment