OPINION: Passion to transform Nairobi City through National and County partnership

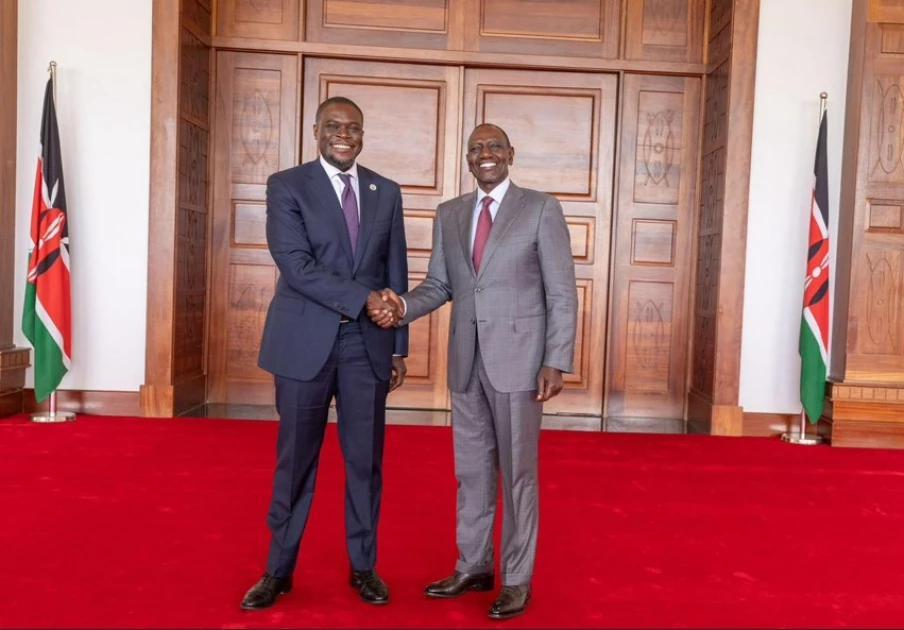

President William Ruto and Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja shake hands at State House, Nairobi on February 17, 2026.

Audio By Vocalize

The Nairobi residents will be the biggest beneficiaries of the partnership between the Nairobi County and the National Government. It is exciting when the law is used and turned toward improving the actual lived experience.

Nairobi is like one zebra with both black and white stripes; if one drives a spear into either the white or black stripe, the whole animal suffers.

Nairobi City, just like a zebra, has both the white and black stripes in the two governments. The agreement is injecting billions into programs that serve the city.

Under the social contract theory, the Kenyan state has an obligation to protect the lives, health, dignity, shelter, and sanitation of all Kenyans, especially the most vulnerable.

In our history of marginalisation, we have witnessed spectres of injustice and inhumanity in various informal settlements in Kenya.

Nairobi City, despite its failures in urban planning, continues to project the image of “a modern, world-class metropolis” by hiding evidence of its weaknesses—managing the visibility of slums, congestion, disorder, disease, drugs, and disaster.

It moves these problems out of sight through the sidelining of the 60% of city residents who live in informal settlements.

According to Stephen Graham in his book *Cities Under Siege*, it is all too easy for politicians to misuse residents of informal settlements.

This is possible because some survive through gifts and sponsorship from politicians. These residents may feel obligated through patronage and become essential components of political campaigns and competitions.

Politicians, in partnership with local actors, sponsor activities such as transport and burial expenses for families in informal settlements.

Often during protests, politicians promise to protect those who have encroached on riparian land along Nairobi rivers from demolition.

Residents live in perpetual fear, with some politicians promising to legalise their residency on public land in exchange for support and loyalty.

Politicians are rarely able to follow through on such promises, and the poor move no closer to full citizenship rights.

For years, they have survived through patron-client relationships that channel votes and mobilise demonstrations when necessary.

As a result of such patronage, some regions and communities have been subjected to cycles of picketing during different political seasons.

Relationships and trust between these communities and formal government institutions, including the police, have been damaged.

Consequently, instances of undue police brutality have occurred, and residents have been stereotyped as violent rioters.

The negative image of criminality and poverty deeply impacts communities such as Kondele, Mathare, and Kibera. For long, residents have endured a criminal stigma that robs them of dignity and opportunities as Kenyans.

They often survive through services offered by politicians, NGOs, religious organisations, and social movements, each with different agendas but the shared objective of “helping.”

Many organisations use informal settlements as laboratories for charity, distributing used clothes and groceries during festive seasons.

NGOs organise communities around housing security, which remains a goal rather than a reality. Often, poor conditions are highlighted in donor proposals for projects meant to uplift lives.

Meanwhile, government initiatives have largely remained invisible in many informal settlements.

This is why affordable housing and protest victims’ compensation programs have the potential to transform the economic and sociopolitical landscape of these settlements and preserve the broad mandates of justice.

These initiatives repair years of underdevelopment and harm suffered by residents of informal settlements, often disproportionately affected by tribal presidential politics.

For the first time, the government considers them as rights-bearing citizens who can gain employment in housing projects within their neighbourhoods and access homes with sanitation and privacy.

The Executive has legitimacy as a promoter of human rights and the rule of law. Accepting responsibility and providing remedies to picketing victims is inextricably linked to the function of the state.

The 2010 Constitution imposes a clear and substantial duty on the state to accept responsibility and provide remedies for harm caused by its actions or those of its agents.

For those who love justice, including advocates in Kenya, there is no need to look far beyond the issues of affordable housing and victims’ compensation.

These programs deserve renewed emphasis through the lens of justice, considering Kenya’s socioeconomic, political, and historical marginalisation.

My plea to the Judiciary and advocates is to reflect on the extent to which they can resist demands aimed at halting economic empowerment through legal practice. In the 1970s, judicial activism in India gave rise to Public Interest Litigation (PIL) or Social Action Litigation (SAL), addressing numerous social ills.

The role of jurists in public interest litigation should challenge mainstream thinking and support marginalised communities.

Leave a Comment