Astronomers get best view yet of two merging black holes

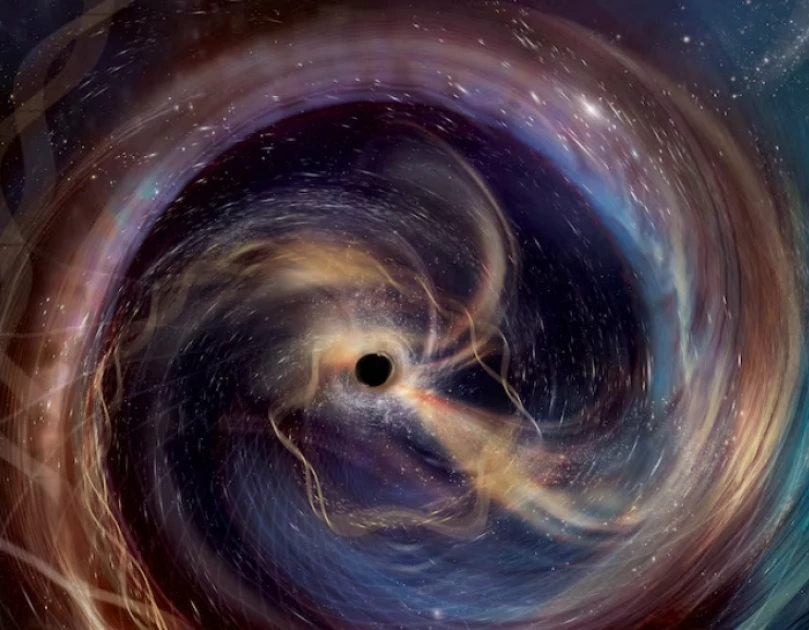

This artist's conception shows events immediately preceding a powerful collision between two black holes, observed in gravitational waves by the U.S. National Science Foundation's LIGO. It depicts the view from one of the black holes as it spirals toward its cosmic partner. The image was released on September 9, 2025. Aurore Simonnet (SSU/EdEon)/LVK/URI/Handout via REUTERS.

Audio By Vocalize

The merger of two black holes is a momentous

event, revealing the wildest and most extreme configurations of space, time and

gravity known to science.

Researchers have now gotten their best look yet at such an

event based on the detection of ripples in space-time called gravitational

waves in an observation that lends strong support to hypotheses from eminent

physicists Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking.

The collision occurred 1.3 billion light-years from Earth in

a galaxy beyond our Milky Way, and involved two black holes - one about 34

times the mass of the sun and the other about 32 times the sun's

mass. They merged in a fraction of a second after orbiting each other at nearly

the speed of light, and left behind a single black hole around 63 times the

mass of the sun that was spinning at approximately 100 revolutions per second.

A light-year is the distance light travels in a year, 5.9

trillion miles (9.5 trillion km). Black holes are extraordinarily dense objects

with a gravitational pull so strong not even light can escape.

The merger unleashed a tremendous amount of energy that

radiated outward as gravitational waves, an amount equivalent to pulverizing

three sun-sized stars. These waves were detected on January 14 at research

sites in Hanford, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana that are part of the

U.S. National Science Foundation's Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave

Observatory, or LIGO.

These observations came about a decade after the

groundbreaking first detection of gravitational waves, which were produced

by a similar merger. Technological improvements since 2015 meant this merger

was observed with four times better resolution than the prior one.

Gravitational waves propagate outward from a source like

ripples in a pond. In this case, the pond is space-time, the four-dimensional

fabric that combines the three dimensions of space - height, width and length -

with the dimension of time.

"Thanks to Albert Einstein, we know that space and time

are intertwined and are best thought of as facets of a single entity,

space-time," said astrophysicist Maximiliano Isi of Columbia University

and the Flatiron Institute, one of the leaders of the study published on

Wednesday in the journal Physical Review Letters.

"This manifests, for example, in that time flows at

different rates depending on where you are: close to a heavy object, like a

black hole, time flows more slowly compared to someone farther away, so that

someone close to a black hole would age more slowly," Isi said.

The researchers analyzed the frequencies of the detected

gravitational waves to discern fundamental qualities of the black holes

immediately before and after the merger. While these frequencies were not sound

waves, the researchers compared them to the ringing of a bell.

"This is just like trying to figure out what a bell is

made out of from the ringing sound it makes when struck," Isi said.

A large iron bell, for instance, makes a different sound

than a small aluminum bell.

What the researchers learned based on the frequency of

gravitational waves offered validation for a basic tenet of scientific

understanding of black holes advanced by Hawking, who died in 2018.

Hawking hypothesised that the total surface area of black

holes - specifically the surface area of the event horizon, the boundary beyond

which nothing can escape - should never decrease. His hypothesis implies that

the surface area of the single black hole produced in a merger should exceed

the combined surface areas of the two black holes that merged.

This merger met that expectation. Before colliding, the

black holes together had a total surface area of about 93,000 square miles

(240,000 square km). The single black hole produced by the merger had a surface

area of about 155,000 square miles (400,000 square km).

"This is the first time that we have been able to make

this measurement so precisely, and it's exciting to have direct experimental

confirmation of such an important idea about the behaviour of black holes,"

said astrophysicist Will Farr of Stony Brook University and the Flatiron

Institute, one of the study leaders.

The observations also provided the most direct evidence yet

that black holes are the paradoxically simple objects foreseen in Einstein's

theory of general relativity, which holds that gravity results from the

curvature of space-time caused by mass and energy.

The findings validated Einstein's proposed simplicity of

black holes - that they can be fully understood based exclusively on their mass

and spin - as worked out by mathematician Roy Kerr in 1963.

The gravitational wave measurements were obtained in a

remarkably short time. Caltech astrophysicist Katerina Chatziioannou said the

black holes were observed spiraling inward toward each other for about 200

milliseconds, and the signal from the merged black hole was measured for about

10 milliseconds.

Leave a Comment