Tech inclusion path for Persons With Disabilities as Kenya's Act promises new dawn

Audio By Vocalize

Digital technologies have been incorporated into people's activities, with access to information and services shifting to online platforms.

Digitisation of services cuts across sectors like health, education, agriculture, commerce, mobility, and manufacturing, among others.

Kenya, for instance, has an ambitious plan to digitise nearly all government services to enable the speedy and efficient delivery of services across the public sector.

However, existing barriers to inclusion prevent persons with disabilities from accessing information and services digitally.

The Kenya Population and Housing Census 2019 showed that 918,270 Kenyans, 2.2% of the population, have a form of disability. This population faces digital exclusion due to a lack of access to assistive technologies needed to live independent lives.

A 2019 survey by GSMA showed that non-disabled persons in Kenya are likely to own a mobile phone compared to persons with disabilities, where the type of disability also determines the likelihood of ownership. Here, the deaf and persons with hearing impairment were likely to own smartphones, while the blind and visually impaired were less likely to have one.

When digital access is denied

In 2022, the Kenya Bureau of Statistics, in partnership with inABLE, developed accessibility standards to guide the use of ICT products and services. The Kenya Standards (KS 2952-1:2022) was set to ensure digital products and services in the public and private sectors are accessible to persons with disabilities.

The standards recommend tactile features in devices, speech outputs, text outputs, visual modes and provision of a mode that does not require hearing. Websites and smart applications should adhere to the global Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), ensuring Interoperability with assistive technology and providing user control of accessibility features.

Even though public and organisations in Kenya are yet to adhere to the Kenya Standards, inABLE’s Executive Director Irene Mbari-Kirika told Citizen Digital that they serve as a platform for the country to build on accessibility and ensure digital inclusion for persons with disabilities.

“We are in progress. Accessibility is not a quick fix, it is not a one-day job. Some companies are taking this on,” says Ms. Mbari-Kirika.

Ms. Mbari-Kirika notes that the lack of awareness has mainly led to the digital divide, where persons with disabilities are excluded from technological access.

By design, creators and innovators overlook the requirements of people with disabilities when developing technological products and services. Without an understanding of these needs, developing technologies that work for persons with disabilities is a challenge, as they become non-inclusive by design.

In policy-making spaces, it is common to hear governments, private sector representatives speak about digital inclusion for underserved communities, often made up of persons with disabilities, older persons, women, rural populations, and indigenous peoples.

However, these vulnerable groups may not only be left out of policy discussions, but also when conducting a market study to gather feedback from intended users of a technology product or service.

Navigating technological platforms

Julius Mbura, a Legal and Advocacy Officer, has a disability - total Blindness. After completing his law degree in 2019, Mr. Mbura lost his vision just before his bar examination.

A tech-savvy lawyer, poet, and car enthusiast, Mr. Mbura uses various digital platforms, including social media platforms, websites, ride-hailing apps, and accessibility platforms like Seeing AI and Be My Eyes.

Mr. Mbura uses a phone or laptop with a screen reader to access the majority of online platforms. His phone has accessibility features for the visually impaired- mainly the voice over from Apple’s screen reader.

“Most of the videos that I watch or listen to online do not have accessible features such as audio description for me to understand what is happening on screen, especially the visuals, because I can’t see them,” Mr. Mbura explains his experience accessing some content platforms.

When a video lacks audio descriptions, the lawyer relies on a sighted person to describe to him whatever is happening on the screen.

Mr. Olubala notes that some audio-visual content he consumes for education or entertainment purposes lacks text transcriptions, hence disrupting his user's journey.

“When the video does not have text captions, I normally skip it and look for another. In some cases, I use the transcriber app for translating voice to text,” Mr. Olubala shares.

Currently pursuing his undergraduate studies, Mr. Olubala takes into consideration built-in accessibility features before purchasing a smartphone, tablet or laptop.

To enhance digital accessibility, the Community Engagement Consultant advocates for transcript text when the content is in video format.

“Also, the recorded videos must have a sign language interpreter box aligning with the flow of the contents,” he notes.

Accessibility in DPI platforms

While Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) are meant to provide economic opportunities and social services for all, disregard for accessibility leads to exclusion for persons with disabilities.

As crucial services in sectors like health and education are increasingly becoming available online, accessibility gaps prevent persons with disabilities from accessing the platforms.

Ms. Mbari-Kirika emphasizes that including persons with disabilities in product design and decision-making will enable access for all.

“Most of these products, you see, persons with disabilities have never participated in their design. You go to universities and they tell you, ‘We have 200 young people with disabilities. And we have online platforms, so now they can use them online.’ But those platforms were never developed with them in mind,” notes the Executive Director of inABLE.

When Mr. Mbura went to law school, the institution provided him with reading materials in soft copy. He would use a screen reader during exams and give extra time to type in his answers. He did not use e-learning platforms.

Both Mr. Mbura and Mr. Olubala access government services online to file tax returns and apply for necessary documentation.

“It is a challenge to access government services because the portals are inaccessible, so I normally depend on my sighted friends to access such,” Mr. Mbura notes that he usually has to seek help to process documentation or file returns online.

When visiting Huduma Centres to access these services, they also encounter barriers. Here, they report, they have not been provided with any accessible electronic device to use. Mr. Olubala notes that “they (Huduma centres) do not offer sign language interpretation services.”

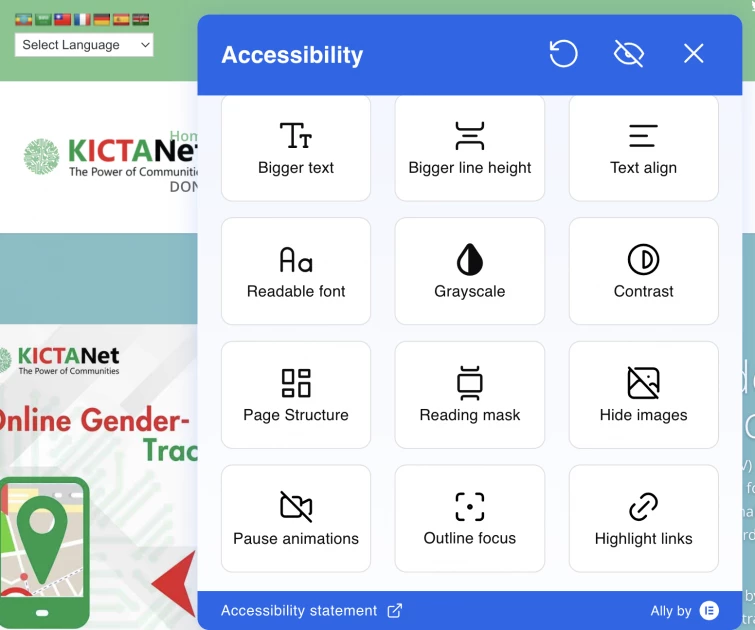

In Kenya, platforms such as eCitizen are meant to benefit all citizens, hence they should be accessible for all. Currently, the accessibility features offered on eCitizen are: high contrast, negative contrast, grayscale, increase and decrease text.

In comparison, KICTANET, for instance, offers more accessibility features on its website.

“Because those are public assets. They are taxpayer-funded assets and persons with disabilities are taxpayers. So there's no reason that we'd be developing a platform which they have funded and they're not considering their user needs.”

Assistive technologies and AI

Emerging technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) solutions are likely to bridge the digital access gap currently facing persons with disabilities.

AI-enabled systems offer new opportunities for disability inclusion through accessibility features like eye-tracking and voice-recognition softwares.

Digital assistants, speech-to-text softwares, automatically generated video captions, image descriptions, sign language avatars are some of the solutions offered by AI.

Assistive technologies, including hearing aids, visual and tactile alerting systems, and telecommunications devices, also have the potential to bridge this gap.

“I use AI almost on a daily especially to get descriptions of my surroundings and in the house when I am doing my usual chores like cooking, or for instance, for my dress-ups in the morning and so on…” Mr. Mbura states.

The Persons with Disability Act 2025

In March 2023, Nominated Senator Cystal Asige introduced the Persons with Disabilities Bill in the Senate, seeking to replace the existing Persons with Disabilities Act. The Bill would also provide a framework for protecting, promoting and monitoring the rights of persons with disabilities.

And in May 2025, President William Ruto signed into law the Persons with Disabilities Act 2025.

This promised a new dawn for the advancement of the rights of persons with disabilities, upholding their dignity, and offering tax reliefs to them and their caregivers.

The act mandates the government to promote the inclusion of persons with disabilities, enhance accessibility to services and assistive devices to promote their livelihoods.

“To fix this, first we need to stop treating accessibility as an afterthought or a special feature. It must be baked in from the beginning — what we now call accessibility by design. This means making sure websites and apps are built to work with screen readers, have alt text on images, offer voice commands, and allow for keyboard-only navigation,” Asigi proposes.

Ms. Mbari-Kirika has termed the act a boost to digital access among persons with disabilities, as it is built on various frameworks, including the 2022 Kenya Accessibility Standards.

She says the Act will support public and private organisations in enhancing digital inclusion.

“It supports the whole accessibility ecosystem. The Act is an enabler of accessibility.

Through the frameworks in the Act, there is hope that access to assistive devices will be affordable in Kenya, where most assistive devices are imported.

Ms. Mbari-Kirika advocates for frameworks to enable local manufacturing of assistive devices to cut costs.

“Most of them are imported from out of the country, and the cost of importation is what drives up the prices for the end user,” she argues.

In her understanding of the accessibility ecosystem, Ms. Mbari-Kirika advocates for a mix of local manufacturing and minimal shipping.

By having a mix, she believes that Kenya will not only have affordable devices, but also those adhering to advancements in research and technology.

The nominated Senator also advocates for specialized training for developers, to enable them familiarize themselves with accessibility standards.

With the National Council for Persons With Disabilities (NCPWD) leading the way, the legislator says various ministries will play individual roles in ensuring compliance.

For instance, the Ministry of ICT could enforce accessibility compliance for digital products used by Kenyans. “Each of these institutions must not only comply, but collaborate, with disabled persons leading the conversation — not just being consulted after decisions are made,” Senator Asige emphasizes.

Leave a Comment