Culture in focus: How African photographers are reclaiming the frame

Audio By Vocalize

In a

continent constantly photographed but rarely seen on its own terms, a quiet

revolution is unfolding through the lens. African photographers are moving

beyond the image as artifact; they are using it as testimony, a layered record

of memory, movement, and meaning.

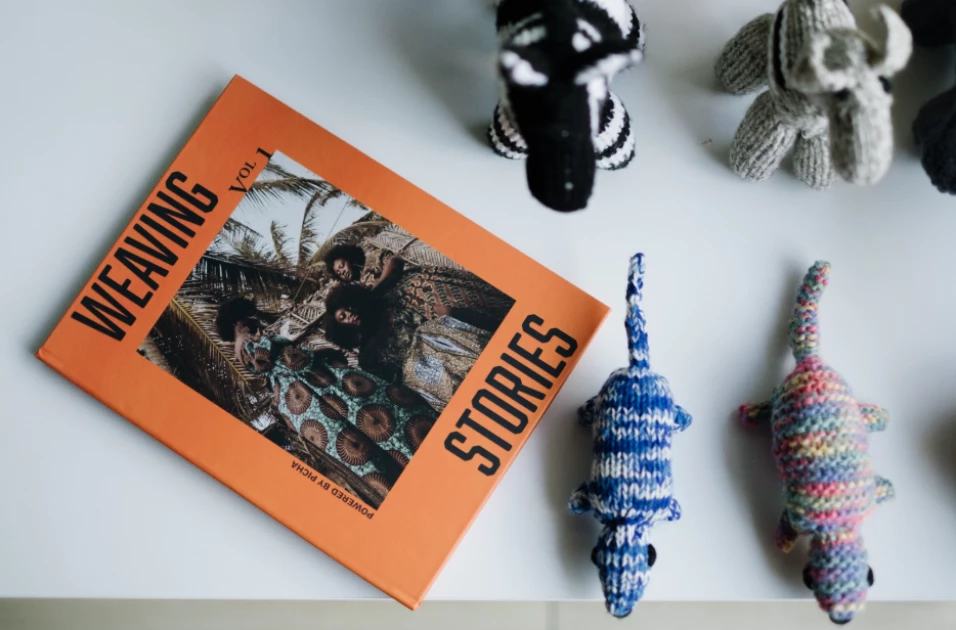

A newly-released

photography book, ‘Weaving Stories’, offers a glimpse into that shift. Compiled

by a collective of Afrocentric visual storytellers, the book threads together

scenes from across the continent and diaspora - not with grand declarations, but

with deliberate intimacy.

No single

narrative dominates. Instead, the collection reflects what life often is:

textured, sometimes quiet, and filled with cultural nuance.

There’s a

woman crouched under the mid-day light, her gaze steady. A boy on a motorbike

with a plastic crown. A family gathered, not for spectacle, but for supper.

These are not images crafted for Western palates or NGO reports, they are made

for and by those who live inside them.

This shift away

from documentation and toward self-definition marks a significant moment in

African visual culture. Where the camera once acted as an outsider’s tool, it

is now becoming a means of cultural memory, wielded by insiders who understand

not just what is in the frame, but what it means to be seen.

Photography

in African contexts has always been more than aesthetic. It has served as

ritual, resistance, archive. Studio photography of the post-independence era from

Malick Sidibé in Mali to James Barnor in Ghana was about more than posing. It

was about presence, about saying: ‘We are here, and we know ourselves.’

Today’s

image-makers inherit that legacy, but their medium has evolved. The rise of

digital photography, social platforms, and community-driven exhibitions has

allowed a younger generation to experiment with what the image can do and what

it can carry.

In Kenya, a

growing number of visual artists are using photography not just to capture

beauty, but to ask questions. What does heritage look like when it’s lived, not

performed? How do we hold onto disappearing traditions without freezing them in

time? What does it mean to photograph a community from within?

The result

is a visual language that’s emotionally grounded and politically aware, one that

does not seek to convince, but to connect.

What stands

out in the photographs featured in ‘Weaving Stories’ and beyond is their

refusal to chase nostalgia. These are not romantic recreations of a distant

past. They are reminders that culture is not a costume worn for tourists, it’s

a living thing.

For Kenyan

cultural worker and curator Nasimango Leilah, ‘Weaving Stories’ represents a

powerful intersection of art forms and a deeply political act of

self-expression.

“PICHA’s

book project ‘Weaving Stories’ appealed to me because it’s a mix of

photography, storytelling, and publishing,” she shares. “Three things that can

be used to tell our own stories, as Kenyans and Africans.”

What stood

out even more, she notes, was the all-women line-up of featured Kenyan

photographers: Barbra Guya, Gloria Mwivanda, Martha Nzisa, and Rading Nyamwaya.

“The topics

they chose were refreshing and defying,” she says, adding; “especially given

the current times in Kenya, when it’s hard to celebrate being a woman due to

the rising femicide and gender-based violence cases.”

This is

where the camera becomes a cultural tool. It captures the rhythm of daily

rituals: hair braiding, cooking, dancing, gathering. These are practices that

carry memories passed down, repeated, adapted. They remind us that heritage is

not always loud. Sometimes it’s the soft clink of utensils at a shared table.

Or a garment passed between generations.

In that

sense, photography becomes a form of quiet witnessing. A way to say: this

matters! Even when the world looks away.

It’s no

accident that this moment coincides with what many are calling the “New African

Aesthetic.” It’s not defined by a single look, there’s no visual rulebook.

Instead, it’s characterized by intentionality. Photographers are asking: who is

this image for? Whose story is it telling? And what truth does it hold?

You can see

this in the works of contemporary Kenyan photographers like Barbra Guya and

Martha Nzisa, who explore femininity, land, and belonging through portraiture

and landscape. Or in the street photography of rising artists in Lagos and

Johannesburg, who frame the chaos of city life with affection rather than

critique. Their work doesn’t explain Africa. It lives in it.

At a time

when so much of African culture is being digitized, exported, and reinterpreted

elsewhere, these photographs stand as anchors. They’re not just about what is

seen, but what is remembered and what we choose to carry forward.

Photography,

in this context, is no longer a luxury or side-art. It’s a form of cultural

authorship. A way of preserving, questioning, and reshaping who we are and how

we’re seen by others, yes, but more importantly, by ourselves.

Leave a Comment