Wole Soyinka’s life of writing holds Nigeria up for scrutiny

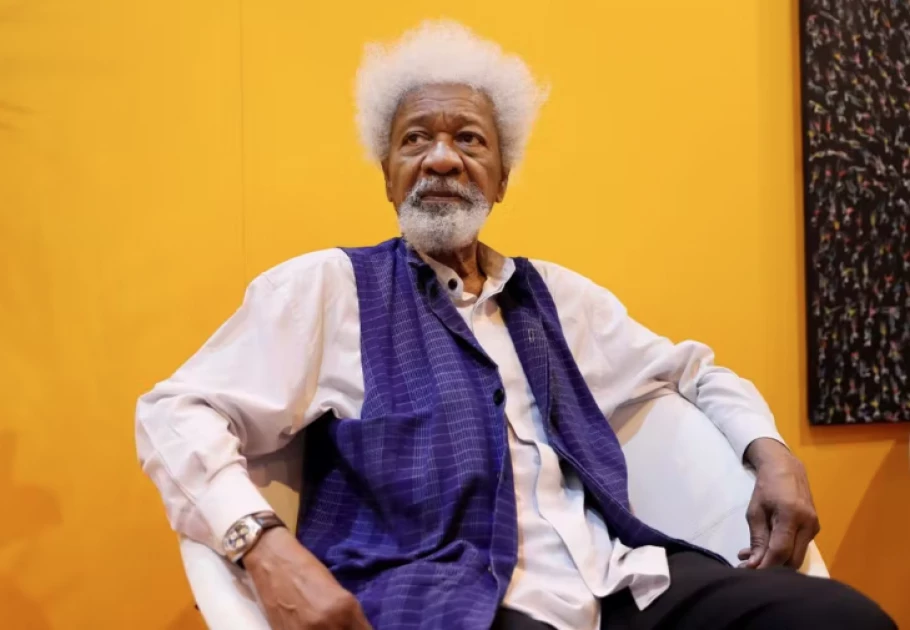

Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka. Thomas Samson/AFP

Audio By Vocalize

Akinwande

Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka, known simply as Wole Soyinka, can’t be easily

described. He is a teacher, an ideologue, a scholar and an iconoclast, an elder

statesman, a patriot and a culturalist.

The

Nigerian playwright, novelist, poet and essayist is a giant among his

contemporaries. In 1986, he became the first sub-Saharan African, and is one of

only five Africans, to be awarded the Nobel

prize for literature. This was in recognition of the way he “fashions the drama of existence”.

His

works reveal him as a humanist, a courageous man and a lover of justice. His

symbolism, flashbacks and ingenious plotting contribute to a rich dramatic

structure. His best works exhibit humour and fine poetic style as well as a

gift for irony and satire. These accurately match the language of his complex

characters to their social position and moral qualities.

His

works have such impact that some of them are used in schools in Nigeria and

some other anglophone countries in West Africa. Some have also been translated

into French.

Life

and activism

Soyinka

was born into a Yoruba family in Abeokuta, southwest Nigeria, on 13 July 1934.

His parents were Samuel Ayodele Soyinka and Grace Eniola Soyinka. He had his

primary education at St Peter’s Primary School in Abeokuta. In 1954, he

attended Government College in Ibadan, and subsequently University College

Ibadan (now the University of Ibadan) and the University of Leeds in England.

He

was jailed in 1967 for speaking out against Nigeria’s civil war over the

attempted secession of Biafra from Nigeria. Soyinka was also incarcerated for

taking over the radio station of the disbanded Nigerian Broadcasting

Corporation in Ibadan to announce his rejection of the 1965 Western Nigerian election

results.

He

joined other activists and democrats to form the National Democratic Coalition

to fight for the restoration of democracy in Nigeria.

He

now lives in Abeokuta.

Themes

and style

My

first contact with Soyinka was in secondary school when we were made to read

his play Lion and the Jewel. Some of my classmates then felt he was difficult

to read and assimilate. I later found out Lion and the Jewel was actually one

of the simplest titles.

Soyinka’s

works often address the clash of cultures, the interface between primitiveness

and modernity, colonial interventions, religious bigotry, corruption, abuse of

power, poor governance, poverty and the future of independent African nations.

His themes have remained constant over time and many African states are still

grappling with issues he has raised since the 1950s.

Through

his works, I discovered that he has deep knowledge and understanding of his

mother tongue, Yoruba. For instance, in Death and the King’s Horseman and other

plays, we see Yoruba wisecracks, philosophy and proverbs translated into his

language of communication, English. These enrich his writings.

I

find the changing forms of his creative works interesting in spite of the

unchanging content of the narratives or drama. Read King Baabu or The

Beatification of the Area Boy and Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest

People on Earth to observe the change in Soyinka’s style.

Forms

of writing

Soyinka’s plays cut across diverse

socio-economic, political, cultural and religious preoccupations. A Dance of

the Forests, one of the most recognised plays, was written and presented in

1960 to celebrate Nigeria’s independence. It reflects on the ugly past and

projects into a blossoming future.

His

1965 play Kongi’s Harvest premiered in Dakar, Senegal in 1966 at the first

Negro Arts Festival. The lead character, Kongi, was played by Soyinka himself.

It deals with themes of corruption, ego and paranoia. The lead character,

Kongi, is the archetype of dictatorship globally. He suppresses all voices of

reason, revelling in his illusion of power and thinking no one can stop him –

until he meets a tragic end.

Other

plays depict clashes of culture between white influence, colonial values and

black African orientations. Soyinka never blames but dramatises the evil people

do through characters with impact, strong plots, accurate settings and

language.

Soyinka

has written only three novels: The Interpreters (1965), Season of Anomy (1973)

and Chronicles from the Land of Happiest People on Earth (2021), which came

almost 50 years after his last. The novels focus mainly on Nigeria and its many

ills, including corruption, religious bigotry and inept governance.

The

characters in the first two novels have dreams which are sometimes dashed

through a tragic truncation of their lives. The latest captures contemporary

Nigeria, the Nigerian diaspora and the myths of an ever-crawling giant. It

paints a picture of things going wrong for the country.

Certain

poems stand out among Soyinka’s collection. These are Telephone

Conversation and Abiku. The former uses humour to talk about the serious issue

of an African experiencing racism as a new student in a British university. The

latter comments on Nigeria’s inability to develop; the poet explores the futility

of life.

Soyinka’s

non-fiction includes The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972), his autobiography, Ake:

The Years of Childhood (1981), Isara: A Voyage Around Essay (1990), Ibadan: The

Penkelemes Years (1989) and You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006). In these works

he has narrated how the story of his life and his family intertwines with the

fate of Nigeria.

As

an essayist and intellectual, he has highlighted the specific failings of

individuals in the Nigerian polity. Soyinka is not afraid of mentioning names

of people he writes about, nor the wrongdoings he is accusing them of.

These

works include Myth, Literature and the African World (1976), Art, Dialogue, and

Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture (1988), The Black Man and the Veil:

Beyond the Berlin Wall (1990) and The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal

Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis (1996).

They

are essays that have contributed to Soyinka’s status as a global intellectual.

[Written by: Abayomi Awelewa, Lecturer in African and African Diasporan Literature, University of Lagos.]

Leave a Comment